I recently wrote a post about the intricacies of shipping items during a move abroad. While outlining how people send their items, I found myself reminiscing about my road trip to Belize –nearly three years ago– from Canada with a load full of belongings to import. It was an eye-opening yet profound experience I’ve meant to write about for some time.

The trip was simultaneously stressful and exciting, highlighted by an unexpected delay at the Texas-Mexico border that completely blindsided my travel buddy and me. There was also a lingering pressure to get to Belize, where my youngest son, eleven weeks old at the time, was seriously ill with a bacterial infection and in a Belizean hospital under rudimentary care, and my wife Lili’s steadfast and watchful eye. With no way to get to them without clearing this massive, unforeseen customs hurdle, I was stranded with my worries and thoughts among two dogs, a shuttle bus chock-a-block full of personal effects, and a travel partner with a finite amount of time to accompany me on this journey.

If you are wondering why I was driving a bus, I encourage the reader to click the link above for the answer.

Sitting at my computer typing and reminiscing, I reflected on why I hadn’t written this story yet. After all, it's an interesting one containing Mexican cartels, a serendipitous turn of events, suspenseful and thought-provoking moments, and grit —common themes I attempt to portray in my other Substack articles.

Over the last few years, I have made several attempts to get this story down “onto paper,” but to no avail. I kept finding myself lost in a sea of seemingly important details that, once written out, were boring. The chain of events was so intricate that I felt the need to shine a light on them all, only to discover the story was convoluted, long-winded, and unengaging.

However, I’ve had enough time away from the event to take a more objective look at the most essential aspects. I have also grown as a writer and now have the ability and confidence to portray all the details in an alluring way.

A Give and Take

Ultimately, I want to reader to take something away from this story amongst entertainment. For those looking for an exciting read, the following contains love, perseverance, determination, resilience, emotional strength, cultural awareness, and, depending on your spiritual bent, destiny, or fate.

From a practical standpoint, I hope that the reader who wants to make the same journey as the one I'm about to describe will get some critical information on what to expect, which will help them avoid costly delays.

One more thing before we get into it: I have refrained from using real names throughout this piece. This story contains sensitive subject matter that the people involved may not want to be associated with in such a public setting. Also, I only briefly met some people in this story, speaking to them over the phone and via text. As a result, I didn’t obtain their information and no longer have a way to ask permission to use their names. In light of this, I've opted to use pseudonyms.

Entering the Land of the Free

The trip down south from the Greater Toronto Area was smooth sailing and uneventful, except for one exception: our crossing at the Windsor-Detroit border. Little did I know that this event was a harbinger for the trip: easy driving, troublesome border crossings, and a sprinkling of poignant moments.

I had entered into the US by land, without issue, before, but being so loaded down, the border officials took a different approach with us. Thinking we would just cruise through, I was surprised when I was asked to pull the bus over and proceed into a small squat building to the right side of the road. I was already a little unnerved as the unflinching officer in wrap-around sports sunglasses told me to pull the fully loaded bus into the parking area. Once parked, he further instructed me to “act like a man” and “leave my purse,” motioning with his nose to the dossier I grabbed containing all my relevant and important documents for the trip and the move abroad.

I had a sinking feeling: they soften you up with intimidation and emasculation before you enter the nearly standing-room-only building, but for what reason? Upon entering, they strategically divided us up. They sent B, my long-time friend and travel buddy, to an adjacent room, out of sight of each other. Devices were forbidden, so you are left only with your thoughts, the sights and smells of the room, and the nervous energy of everyone around you. As I stood there attempting to gain my bearings, I saw this split-up tactic repeated on families with tweens, elderly couples, and husbands and wives. You were only reunited upon questioning.

Enter Interrogation to Exit

In this hot and stuffy room, a panel of officers behind slightly elevated kiosks —which forces you to look up at them— interrogates everyone in attendance in a seemingly random and disorganized manner. Their sporadic line of questioning is bizarre and irrelevant but also stress-inducing. They call you up, and your selected officer, seated next to the passport you handed over to the ultra-masculine, sunglassed man, asks you a few random questions through a glass panel. “Where did you go to elementary school?” and “What did you study in college?” they ask, slightly muffled by the pane so that you must awkwardly lean an ear forward to hear. After you respond, the high-seated officers send you back to your seat, provided you are lucky enough to snag one.

My nervousness grew, and my mind began to spiral. “What happens if I get caught in a lie?” I thought.” If I get denied entry, I’m screwed!” I hadn’t exactly been honest. I hadn’t made any official claims about moving abroad. My license still had my old address: a house I no longer owned, having closed on the sale less than two weeks prior. I took a deep breath… but not so deep as to make it obvious that I was doing so. After all, I could feel the unseen eyes peeping at me, watching my every move, and there was no need to draw any unwanted attention.

United We Stand, Divided We Leave

It is an unnerving experience. Yet, eye-opening and humbling. All races, genders, and creeds were corralled and tightly packed into this building —it must have violated some occupancy capacity. We were all here under the same pretense: probably guilty of some yet-to-be-determined crime or infraction. I was placed shoulder to shoulder with Black, Central, and East Asian, West and Native Indians, and Hispanics. We were all one in our nervousness, sharing furtive glances, fleeting nods, and feigned, brief smiles in an attempt to comfort one another.

A world within itself, all members shared the same unsettling experience: needing to prove to the US border authorities that you hadn't done anything wrong and that they should give your passport back and let you go. As a Caucasian male, it gave me a glimpse, albeit brief, into a world that many others experience daily because of their skin colour, gender, cultural background, or systems of belief. I was grateful that this wasn't a regular part of my life, and I felt deeply for those for whom it was.

After a few rounds of interrogation spanning nearly three hours, the experience ended as abruptly as it began. Virtually mid-answer, we were handed back our passports and told we could leave. We left with urgency and gratefulness, trying not to make contact with the jealous and longing eyes of those who entered along with us.

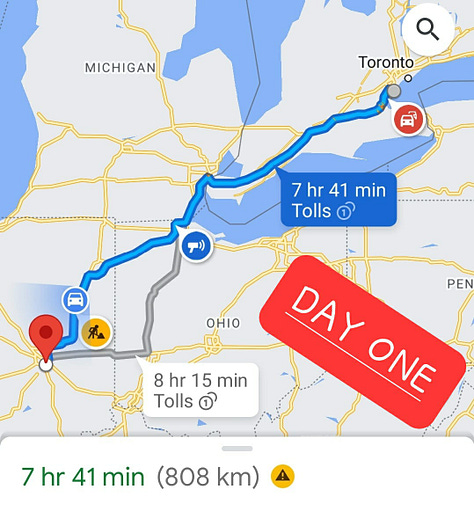

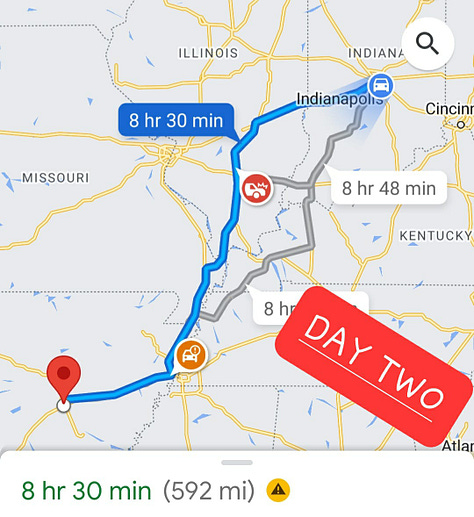

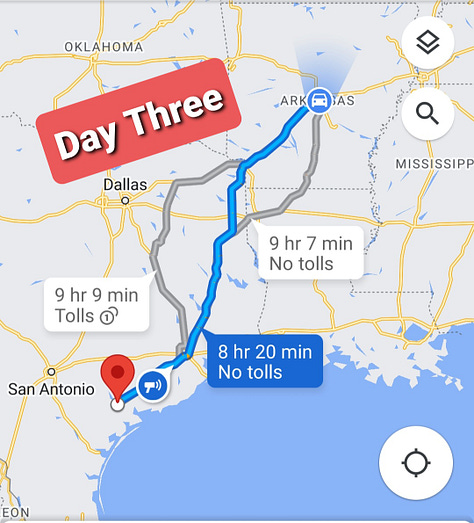

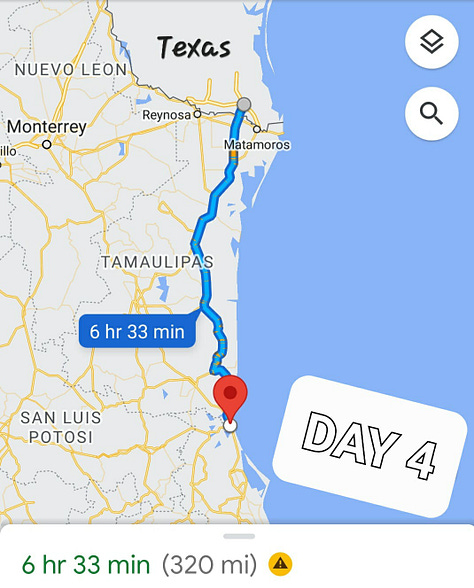

The trip through the US was easy and uneventful. We drove seven to eight hours a day, leaving early in the morning and arriving at our destination mid-afternoon with enough time to rest, exercise the dogs, and find somewhere to eat. We stopped in Indianapolis on night one, Little Rock, Arkansas, on night two, and the outskirts of Victoria, Texas, on night three, several hours from the Mexican border. We were so confident in our schedule and timing that we were caught completely unawares when we hit the border at Brownsville-Matamoros in the late morning of our fourth day on the road.

Trying to Crossing the Rio Grand

“The Rio Grande is more than just a river. It is a line between worlds, between cultures, between dreams.”– Charles Bowden, author and journalist.

After a quick bathroom break for us and the dogs and a visit with a money exchange to swap some dollars for our toll route pesos, we paid our small stipend to exit the US at a lift gate entering the bridge. Navigating curbs and barriers not designed for a vehicle of our size —we would later find out that larger vehicles like mine aren’t allowed to cross the BV-M border, although this wasn't the reason for the yet realized delay— we rolled onto the bridge.

Not knowing the hardship about to befall us, we excitedly looked over the bridge parapet at the waters below. A new leg of our journey was beginning, but it wouldn’t be in the way we had anticipated.

As we approached a set of booths on the road median, an arm extended from a window, motioning for us to stop. We complied and shelled out another small fee before the gate separating us from the road ahead lifted. Rolling through, armed guards waved us forward, and in traffic control style, directed us to a parking area with straight, circling arms.

I parked, and guards appeared along both sides of the bus. They said something in Spanish. Thankfully, B understood— after spending several years working abroad in Costa Rica.

We need to get off,” he said, “You need to go in that building,” pointing to a set of doors diagonal to our front right bumper. “I'll take the dogs,” he continued as I grabbed my ‘purse’ of critical information. For anyone looking to make this trip, it's essential to have your vehicle ownership (you must own it, not lease it) and any other relative information about you, your family, and your pets handy. You will need it.

I entered the building and approached the immigration desk. I pantomimed through the conversation, which ended in both B and I getting our visitor permits— seven days: more than enough time for our three days of planned travel. This would come back to bite me.

After immigration, I moved to an adjacent window for the temporary vehicle permit. I already had my insurance but had issues completing the permit process online. It quickly became apparent that something was amiss. The officer behind the booth exited his station and proceeded outside to discuss something at length with his counterparts.

Fuck, We’re Stuck

He returned with another officer who could speak English and explained to me as best he could that we couldn't cross here and needed to go to another border. I didn't understand and continued to mime through the conversation, relentlessly feeling up an imaginary wall, hoping to find the top to look over into assumed clarity. It was no use. There was no convincing them. I left frustrated and confused; the word ‘Transmigrante’ but a gossamer fluttering from a draft in the wall of my understanding.

I returned to the bus, thinking the border officers told me we were too big and needed to cross at a different border rated for vehicles our size. This request seemed simple enough, albeit annoying, and posed only a mild hiccup. We crossed back over the Rio Grande bridge, shelling out another set of fees, and made our way 45 minutes North-West to the Los Indios border crossing.

We reached the new border around 2 pm. I paid the tolls at this Rio Grande Bridge and again crossed into the Mexican no-mans land between the two nations. All I had known was behind me, and in front of me was a new life, new experiences, and a new understanding of the realities of our world.

Along the right-hand side of the road was a meandering line of vehicles —pickup trucks, cars towing cars, and tractor trailers, all loaded to the tits— that veered to the right, through a guarded gate and into a parking area where more vehicles arranged themselves in hodge podge lines. It was hot as hell, and B and I reciprocated a glance that said, “Glad that's not us.” Little did we know that it soon would be.

The Mexican Government Doesn’t Care

We continued straight along the road, and then men with automatic weapons flagged us to pull over into a parking area, similar to the previous border. B exited the bus with the dogs again, and I headed into yet another immigration building. I won't bore you with repetitive details: the outcome was the same as our first attempt, but I understood our predicament this time —the Mexican government was denying our entry. Based on our vehicle and its contents, we were Transmigrante, and as such, we needed a customs broker to provide us with the necessary paperwork to pass our “goods for sale” through their country. From what I gleaned from the conversation, there was a broker on site, but since it was already 2 pm and they closed at 5 pm, there was no way I would make it through the epic line of vehicles before the end of the day. The best I could do was try again tomorrow. I tried to explain that the bus contents were all personal items and not for sale, but they couldn't care less. I was transiting through as a Transmigrante, and I needed to act like one.

So, What is a Transmigrante?

For those who don’t know, which is pretty much everyone I talk to about this, a Transmigrante is the small demographic of Central Americans (mostly men) that purchase used items in the US and drive them through Mexico to their home counties for resale or upcycling. They haul almost anything, from wrecked vehicles and automobile parts to electronics, clothing, and used appliances.

Apart from my skin colour, native language, and intention for my items (meaning, not for sale), no other distinguishing characteristics separated us from the definition of a Transmigrante. Now, I think those are significant; however, as I said, the Mexican government didn’t care. We looked exactly like one, driving an old shuttle bus with household items rammed from floor to ceiling and from front to back. We had to follow the path of the Transmigrante through Mexico.

And that's what the queue of vehicles we saw earlier was —fellow Transmigrante looking to pass through Mexico to their home countries in Central America. It was an eye-opening experience for me. Not only had I never heard of such a thing, but to find out I was one was dumbfounding.

Comin’ Up Sin Nada

I researched this trip extensively and perused endless Facebook feeds and Google searches in my investigation. I never came across the term nor read any account of a North American being deemed one. All my research pointed to fellow Americans and Canadians moving south with a vehicle or trailer full of stuff, just cruising through the border as any old tourist would. That was not the case for me!

Even after doing a retroactive search months later —I was determined to find out how I overlooked such a significant detail— I still couldn’t find much information. All I could dig up was some US government website references and a couple of news articles from small-town Texas publications. I even searched again while writing this two-and-a-half years later and still couldn’t find much. Facebook revealed a handful of Transmigrante Groups and the odd reference to their unique way of packing goods but nothing about a non-Central American becoming one.

I returned to the bus defeated yet again. With my head spinning, B took the wheel so I could figure out what our next move was. We crossed back over the Rio Grande into Texas for the second time, shelling out another set of fees for a total of eight that day. I found us a place to crash for the night in Harlingen, the closest major area with hotels accepting dogs as guests.

Once settled at our accommodation, I got to Googling customs brokers and sent an email to the American one I had hired to handle our customs entry in Belize. That was an immediate dead end, as he, unfortunately, only had contacts in Texas ports, not land borders. I was on my own.

By this time, it was 5 pm on May 26, and no customs brokers were answering the phone, except one who promptly told me, “Tomorrow is Memorial Day, and most brokers will be closed until Monday for the long weekend, even the ones at the border.” I maintained my efforts, undeterred by the impending holiday. I began calling Spanish-speaking brokers, but since I didn't speak the language, I got nowhere with them. Miming is essentially impossible over the phone. I was even hung up on several times.

My frustration grew. “Aren’t we in the US?” I exclaimed to B, “An English-speaking nation, and they can’t speak it?.” It was ignorant and hypocritical: I was entering Mexico and couldn’t speak Spanish after all. So, it appeared that the local population of Spanish brokers was not interested in conversing with a non-fluent gringo. As the day wore on, the sinking feeling that I was no closer to finding a customs broker came crashing in.

Palm to a Face Full of BBQ with a Side of Bread

“Fuuuuuuuuuuuck,” I thought. “We’re stranded for at least three days,” I told B, trying to hold back my frustration. That frustration soon turned to fear, as the next evening, I received a troubling text from my wife: Dash, our youngest and only eleven weeks old, had a sustained high fever that wouldn't break. She was taking him to a private hospital in Belmopan for medical care, which required a two-and-a-half hour drive through dark and winding, unfamiliar mountain roads. I felt gutted. And hopeless. My family needed me. But I was stuck in Texas, classified as something I was not, while America partied. I'd never felt so powerless. I was at the whim of the unknown. I had been on a similar precipice before when leaving my first marriage and with the birth of my first son. I had become somewhat of a veteran of the unfamiliar. Nevertheless, I didn’t like it or cared to face this abyss again.

During the debacle that unfolded for Lili while getting Dash the care he needed, a local police officer tasked a young boy to get some bread dough from a local bakery. The officer advised my wife to wrap the dough balls around Dash’s tiny feet: some sort of old-timey remedy for drawing out fever. You may think this sounds like bullshit, but my wife swears it contained his fever during the drive north to Belmopan. When they arrived at the hospital, the dough was baked.

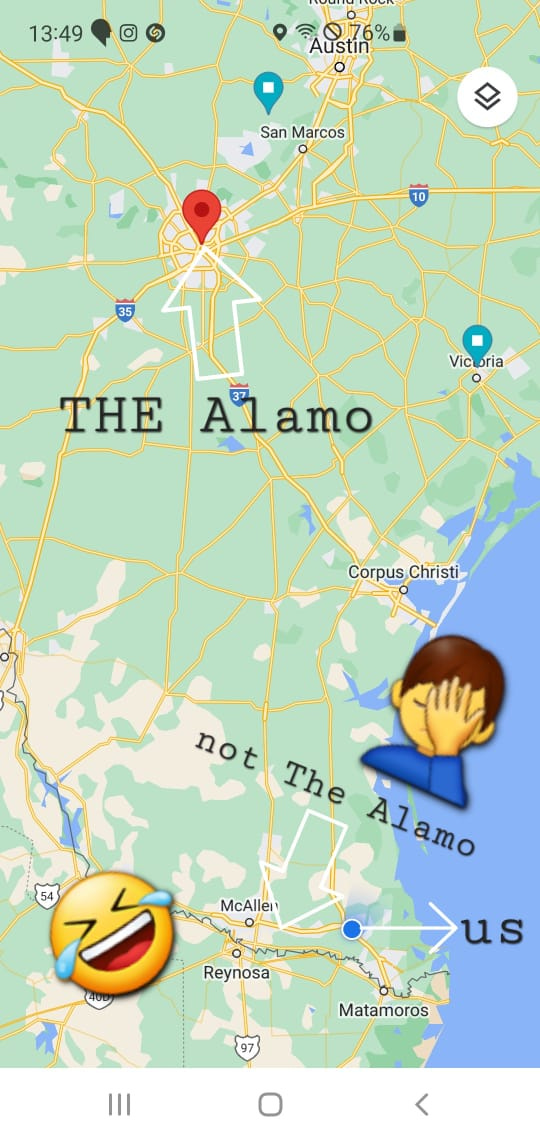

B and I spent the weekend exercising the dogs, researching the next steps, making phone calls (in vain), and eating Texas BBQ, anything to keep my mind from wandering too far into catastrophe. Amidst the stress of the situation, a funny thing happened. While looking for things to do in the area, I came across Alamo, Texas, and thought, “No way, The Alamo is close by?! We might as well take in some history while stuck here.” Google Maps said it wasn't more than an hour away, so B and I hopped on the bus and headed to the Alamo… well, not exactly. We ended up in a random town next to the highway, indistinguishable from any other town, named Alamo. Not The Alamo. Just Alamo

, and certainly not the site of Davy Crockett's 1834 standoff with the Mexican Army. The Alamo is in San Antonio, 250 miles north-north northwest of where we were staying in Harlingen. *Face to palm* Perhaps this error indicated where my mind was at —distracted. We stopped at a BBQ place on our way back and called it a day.

I cannot sit idle, especially amid an ordeal, so once we were back at the hotel I resumed making calls and managed to get through to several brokers. It was Saturday, and they were busy coming off the Friday holiday, telling me they couldn’t get to my paperwork until later in the week or early the following. No bueno, I needed to get into Mexico asap.

A Glimmer of Hope in the Dark Night of the Soul

“Trust that all is for the best. For we carry our fate with us—and it carries us.” —Marcus Aurelius, Stoic Philosopher and Emperor of Rome, 161 to 180 AD

That evening was more troubling news from Lili. Dash was in rough shape: his blood work showed his C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were highly elevated, a sign of a serious bacterial infection ravaging his little body. Typical levels are 1-10 mg/L, but Dash’s were over 100 mg/L. Lili was beside herself, and I was scared shitless. I tried to keep it together, stay positive, and not let her know how terrified I was. I needed to focus and get us out of Texas and back on the road. As horrible of a call as it was, there was a silver lining: Lili reminded me of someone who could help us get through Mexico.

A Knight in Shinning Plaid

Rewind about a month. Lili and I are at our lot in Placencia, waiting to meet the man who will deliver our prefabricated home to its site across from the beach. He was a Mennonite (of the more liberal persuasion) named Eric and had a unique business delivering homes for prefab builders countrywide. We wanted to meet him to ensure there wouldn't be any issues accessing the property on delivery day. If you are interested in this process, check out this blog post.

He agreed to meet us on a Saturday and brought his wife, who had a sister in the area, along. They were a lovely couple in the standard cultural garb: he in a hat, jeans, and a plaid shirt, and she in a printed full-length dress. We got to chatting, and during the conversation, we fell into the topic of my drive from Canada to Belize, which I was undertaking in the coming weeks. Eric informed me that he had a brother-in-law, Billy, who had made the trip several times and could assist me with driving through Mexico. I could pay for his flight to Texas, and he would drive with me through to Belize. Eric explained that Billy had a lot of experience with this trip, having transported vehicles and ATVs, and even had a couple of run-ins with the cartels. Since he paid a ransom the first time, the cartels let him go the second time around —an honest mistake apparently — as once you've paid a ransom, you are not to be touched again. Apparently, the cartels have some sort of honour system, so I'm sure it didn't end well for the poor fellow who decided to pick up Billy that second time.

Since I had B coming along already and had crossed my Ts and dotted my Is —so I thought— I didn't think much of the offer but to say thank you and file it away in the part of my brain that doesn’t take shit seriously. Had I known the trouble we would run into, I would have immediately taken him up on the offer.

So, that interaction with Eric a month earlier is how I found myself texting Billy on the morning of our third day stuck in Texas, asking him to help me get through the Mexican border.

Cosmic Puppet Master

Now, this is where things get a bit surreal. The preceding chain of events is beyond serendipitous and makes an agnostic writer like myself reexamine a belief in a higher power. A grand puppet master must have been tugging at strings behind the curtain of my perceived reality.

Moments of Perfect Timing

I waited around impatiently for the better part of two hours, fixated on my phone like a junkie waiting for his dealer to call. When the screen lit up with a notification, I immediately grabbed it. It was Billy. Contained in his brief message, which read, “Call this number, he can help you,” was the contact info of someone named Humberto. I texted Billy an appreciative thank you, added Humberto to my contact list, and immediately called him. It rang several times and connected with a voice on the other end, “Hola.” “Hola,” I responded and told him my name, my predicament, and who gave me his number.

Humberto responded at length, in Spanish, none of which I understood. After he finished, I said one of the few Spanish phrases I learned for the trip, “No hablo español.” There was silence before he said something quickly, and then all I could hear were muffled voices. I waited for what seemed like minutes when suddenly, an English-speaking man was on the other end of the line. He said his name was David that he was just crossing the border into Mexico and would call me back on my number (which I gave him) once he had crossed through in about thirty minutes. With an emphatic thank you, I hung up.

I wasn’t sure what had just happened. Had Billy given me the name of a Mexican border official? Billy knew I didn’t speak Spanish, so how would he help me if we couldn't understand each other? I decided to set those thoughts aside and be grateful that he had handed the phone over to David, a seemingly random passerby, who offered to help me.

About an hour and a half passed before I began to feel like an idiot for not getting David’s number in return for mine. Feeling abandoned by a man I didn’t even know, I felt the air leaking from the tires of hope. Back to the drawing board, I thought, as I frantically scanned my email for responses from brokers and rehashed Google searches, looking for contacts I may have missed.

My phone rang. It was David! David was a Belizean transmigrant, and he was on his way home with a used vehicle and other items for resale. After a brief conversation in which he explained the processes and provided me essential tips, like claiming that you will return your vehicle to its country of origin to save the costly duties on it, he sent me screenshots of all the paperwork I would need. He also gave me the contact information of the Spanish-speaking customs broker he used, which he emphasized as a necessity. The relief was indescribable, yet I knew this was only part of a greater effort to get what I needed. I thanked David profusely. His generosity and compassion were startling. He didn’t know me and certainly didn’t owe this foreigner anything, but he went out of his way to help a random gringo stranded in an unfamiliar state with a lone wife and sick baby more than 1300 miles away.

After hanging up with David, I immediately called the customs broker he recommended. They were Spanish-speaking, and I struggled to explain my situation. In broken English, the woman on the other end of the call told me she would call me back and hung up. I had an uneasy feeling. Why did they need to call me back? I was also a bit suspicious as I was pretty sure I had called this broker in my previous attempts to get a hold of one. I had essentially called every broker in south-eastern Texas and couldn't shake the feeling that my only solid lead was attempting to shrug me off.

I couldn't lose this opportunity. I had to get them to process my paperwork; they were my only chance to get out of Texas. I decided to give them the benefit of the doubt and wait one hour for them to return the call. It was 1 pm, and Google said they closed at five. By two, they hadn't touched base, so I decided to be unignorable. Their office was forty-five minutes away, close to Alamo. They won't be able to ignore me in person, I thought.

B waited in the bus while I gathered my documents to take into the small flat-roofed building in a commercial/industrial area on the edge of some random highway-side town. I caught a glimpse of a tractor-trailer and other heavy equipment in the yard down a driveway to the left of the building as I entered through the heavily tinted glass doors. There were three women behind desks. I introduced myself as the one they had spoken to on the phone nearly two hours ago. They laughed amongst each other, sharing eye roll glances. My suspicions were correct: they did not intend to call me back. But now I was face to face with them and wouldn't take no for an answer.

Another Mennonite Saviour

I engaged in my regular pantomime in place of my lacking Spanish. It was a struggle. The women could understand me, but they didn't have the English-speaking skills to communicate effectively.

Then, a bearded, tanned Caucasian man emerged from a dark lounge adjacent to the office the women and I were in. He had overheard our conversation and struck up one with me. The tractor-trailer I saw in the back turned out to be his. The machinery he was hauling had been denied entry into Mexico because he wasn't the owner. He had been stuck in Texas for longer than I had, while the Belizean owner found his way to Texas to claim ownership before it could pass through. He wasn't a Belizean Mennonite, as I was familiar with, but a Mexican one who spoke fluent Spanish and English. As he and the women and I engaged in a conversational ménage à trois, he translated for me, relaying all the details I failed to grasp due to the language gap. Without him, I don't know if the ladies would have completed my paperwork in time, as it was five minutes to five pm when I left, and the previous conversation with the women was speckled with claims of “we may not be able to finish this today.”

Despite my lack of Spanish, I still understood a reference to Billy in their discussions. How they knew that I knew Billy was beyond me. After all, I called Humberto, who passed me off to David. I asked them how they knew Billy, and they smirked. I didn't need to understand Spanish to read their faces: every gringo that came through their office led back to Billy.

Before I left, and after shelling out 1,000 USD, the women gave me an 8.5 x 11 manila envelope containing three copies of the paperwork, a ‘Transmigrante International’ bumper sticker and $87, which was cut from the thousand I gave them. One of the women directed me to place the sticker on my front bumper and to give the money to Humberto. “Humberto?” I exclaimed, “I know Humberto.” The woman nodded, smiled dismissively —knowing I did not— and shooed me out the door.

Third Time's a Charm: Crossing the Rio Grande Again

“‘...the end of Texas, the end of America, we don’t know no more.’” —Neal Cassedy, in On the Road, by Jack Kerouac

We queued up in a long line of beat-up cars and trucks just before the Rio Grande bright and early the following day. The sun was rising, and it was getting hot. The line of vehicles began to creep forward. We crossed the bridge once again, praying it would be our last. There were men on the road directing traffic. A scrappy-looking middle-aged man dressed in a military-style camo bucket hat, a long-sleeved dry-fit shirt, and a crossing guard pinny flagged us down and directed us to pull over.

Walking around the bus's passenger side, he motioned to me to open the side door. He stepped on board and spurted out a quick sentence in Spanish. As you can guess, I had no idea what he said, but luckily, B did and replied that we only spoke a little Spanish. “Why are you in Mexico if you can't speak Spanish?” the man said in fluent English with a thick Spanish accent.

I was relieved he could speak English, but his presence made me uneasy. He exuded an authority, which I found confusing. He bore no official uniform or crest, but it was clear that our entrance into Mexico hinged on his approval. I told him we were just passing through on our way to Belize. Ignoring my previous response, he questioned, “Where did you get that sticker?” referring to the ‘Transmigrante America’ sticker I stuck to the driver-side front bumper earlier that morning. “The customs broker,” I replied. He demanded I call them, pointing to the melamine folder with the customs broker’s number stamped on it. I was flustered but complied. I didn't understand what was going on. The phone rang several times, and then one of the Spanish-speaking women answered. “Hola, this is Simon. I was in your office yesterday…” the man snatched the phone from my hand before I could finish. He launched into a fast-paced Spanish conversation with the woman on the other end. I looked at B. B looked back. We said nothing but telepathically agreed to hold our breath.

Is it Hot in Here, Or is it Just Me?

The temperature on the bus began to rise. It was still early in the morning, but the open asphalt road radiated the heat from the previous day. The dogs panted heavily. I was surprised by their resilience with the long days of travel on the stuffy bus that didn't have AC. It was hot as hell, and we couldn't open many windows because of the tight pack of belongings inside.

We were sweating our balls off in no man’s land as the man spoke to the customs broker. We were no longer in the US, but not really in Mexico yet. It wasn't my first time being in such a place —I traveled to Southeast Asia in my early twenties and experienced a similar place between Thailand and Laos. No matter where in the world, it's the same feeling: a strange sense of being neither here nor there. And these places always contain shady characters. We waited. B tried to glean something from the conversation but struggled with its speed.

The conversation between our new passenger and the customs broker ended. He returned my phone and gestured for me to speak into it. The woman on the other end said, “Give him the money,” in a thick Spanish accent. “I thought it was for Humberto?” I replied. “Just give it to him,” she said dismissively and hung up. I reached into the envelope she'd given me and pulled out the small fold of US dollars. I handed it to him, and he placed it in his shorts pocket without counting it, apparently taking advice from Kenny Rodgers. Yet, I got the impression he knew the amount already. This was routine. He motioned toward the paperwork with an impatient wave of the hand. I passed it to him. He rustled through the papers, looking up at me and then at the contents of the bus, examining it for continuity. He said something to a man who had materialized outside the driver-side door —very sneaky, sir. He took one of the three copies, handed the other two back, and told me to open my door. The second man plucked the papers from my hands, looked at them, and cranked his head ninety degrees while looking at the door frame. He confirmed the VIN and returned the papers with a nod to his partner on the bus. “You can go,” the man on the bus said as he stepped off. He motioned down the road with an outstretched arm and a slight bend at the waist.

I closed the doors and the gravity of the situation hit me. These men weren't any sort of border officials. I had just dealt with a cartel man. I looked at B and said, “What the fuck did we get ourselves into.”

So, Who is Humberto?

I learned that day that Humberto isn't a real person: it's a code name for these cartel dudes on this stretch of road. And there are lots of them, too. They take possession of a list of all the belongings a Transmigrante carries, the value, and even the VIN on their vehicles. If they wanted to roll me or anyone else down the road, they would know who and what to look for and how much it's worth. Our saving grace was the sticker on the front bumper, which signaled to the cartel spotters that we paid our dues and were cleared to pass. Institutionalized corruption at its finest. All in a day's work, just across the Rio Grande.

I should correct myself; our saving grace was not the sticker but David. Billy had provided me the phone number of a Humberto—not the same man I had on the bus that day as he spoke English, thankfully. Yet, fate would have it that David, an English-speaking Belizean with a heart of gold, would just so happen to be there when I called the cartel man.

Ingrained Unscrupulousness

At the time, I wasn't clear on the whole situation. I didn't have time to consider it either; we still had 1300 miles to cover. But after taking some time to process what happened, I recognized a level of deep-seated corruption in broad daylight and literally under the watchful eye of both the US and Mexican governments, and it shocked me. I was naive for sure, but this experience revealed that such things are an accepted fact of life along the border and that of the Transmigrante. I’d witnessed corruption during my travels over the years, mostly drug-dealing local cops and extortion-prone police officers, but nothing at this level.

It makes you wonder how the US government's complacency lends to the proliferation of such things. It also makes you realize how embedded seemingly civilized governments are with organized crime, both north and south of the US border. There is no way that US border officials are clean-handed in all of it, given how closely they work beside this culture and industry. Otherwise, either nation would have stopped the dues collecting a long time ago. Because that's what my 85 dollars was: dues, an unofficial toll, a bribe collected by a cartel. Call it what you want, but the Transmigrante must pay it to enter Mexico. I can only imagine the untold millions it produces each year.

On the Road Again

We were moving again, and It was a relief, but we weren't clear yet. We still needed to get through the official Mexican customs. We pulled out of the rusted, jumbled queue and headed down the road. Armed guards directed us away from the regular border crossing towards a large fenced-in parking lot where hundreds of vehicles would soon be packed in like sardines in the hot, unobstructed sun. We found a place towards the front of one of the many forming rows. We turned the engine off and waited—vehicles packed in around us. Monstrosities of diesel and garbage hemmed us in on all sides. Tractor trailers hauled wrecked dump trucks; in their dump bodies were smashed-up pickups with old appliances in their beds and tattered items falling out of the cab, like some post-apocalyptic turducken. Cars towed others, with nothing but a rope as a tether and a sign cautioning “in tow.” All the “goods” surrounding us were heading south to be repurposed, resold, or upcycled.

It was a mind-blowing experience. I had no idea such an enterprise existed nor that a class of our modern society lives this way, participating in a trucking industry straight out of Mad Max. It's an industry pegged to a real-life caricature of the saying, “One man's trash is another man's treasure.” It's also a daunting reminder of how much trash we in North America produce. And a harsh glimpse into the realities of life outside of a developed nation. It also made me question what “developed” truly is. —from what I can tell, the distinguishing feature is a national wealth high enough that its citizens can purchase throw-away products manufactured in lower-income countries and then leave the waste management to those same countries. It's the privilege to play ignorant of the waste we produce. I digress.

Ain't No Time Like Wasted Time

The lines slowly moved forward as cohorts of vehicles made their way to a depot through a gate up ahead. We assembled with the other vehicles inside the fence line when it was our turn. All the drivers got out and queued to speak with an American customs official. I didn't understand, wasn't I in Mexico? I thought. Why was I back to dealing with US border officials?

When I finally approached and handed the officer my paperwork, he looked at me and said, “You don't need to be here; this is customs brokerage. You have your manifest and valuation already. You can go straight down that road.” He motioned with his hand to that same road we drove down after paying off Humberto, except we didn't need to enter the sizzling parking lot with the other vehicles. We could have continued down and around the steamy asphalt clearing.

“So, I didn't need to be in that line?” I asked him, pointing to the area we had just spent four hours in, surrounded by heaps of hot metal and rubber. “Nope,” he replied, calling out “next” as he reached his hand past me to grasp the paperwork of the next anxious Transmigrante in line.

I took deep breaths as I made my way back to the bus, attempting to calm myself down and forget about the four fucking hours we just wasted sweating in the hot Mexican —or American, I didn't even know what country I was in at this point— sun, while my youngest was laid up in a Belizean hospital with my beyond worried wife. I jumped back on the bus and continued to another depot, where the real Mexican customs officials were.

Duck Duck Go

We pulled into another queue and waited for a customs officer to arrive. They didn't. Time ticked by. There was no rhyme or reason for how they processed the vehicles. Someone would pull up and almost immediately see an officer while others sat parked for hours. Most customs officials had a trail of Transmigrantes following them, like a string of ducklings attentively following their mother while waiving their paperwork like Wall Street brokers on the trading floor, in a desperate attempt to get their attention.

I restored to the same tactic and eventually cornered one trying to deke behind a tractor-trailer to lose his tail. I popped out in front of him with my papers in one hand and an outstretched arm blocking his path. I directed him to our bus two rows over. He leafed through the manifest while quickly looking at the contents inside the bus. He scribbled something on one of the remaining copies and advised me to proceed to a building flanking the yard. I bounced between a few kiosks within the building, paying fees, and then moved outside the yard to the immigration building. They looked at my passport and handed it back immediately. I didn't question it and hurried back to the bus, forgetting that our passports had been stamped with a seven-day visa four days prior.

Belize-Bound and Down

We fired up the engine and maneuvered the bus through gaps in the surrounding vehicles, inching our way past the metal monstrosities. After a quick pass through fumigation, we were once again Belize-bound. We pulled over briefly to let the dogs out for a pee. It was 2 pm, and they had been patiently cooped up on the hot bus since 5 am.

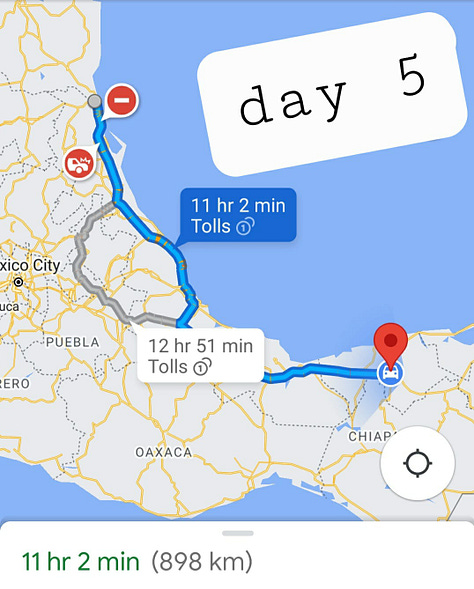

We were ecstatic and relieved to be on the road in Mexico, but we still had a solid six hours to our night stay in Tampico.

We arrived in the city after dark, bleary-eyed and road-weary from the fifteen-hour day. I called Lili immediately. Dash's situation had worsened: there was now blood in his vomit and diarrhea. Her shaky voice subtly told me she was trying to keep it together. Feeling inspired by the serendipitous events, the good fortune, and the kindness of strangers, I told her I knew everything would be okay. “The universe didn’t just put me through the wringer so that Dash could die in a simplistic Belizean hospital while I was still over a thousand miles away,” I said. “The way things unfolded in the last 24 hours was proof that things were moving in the right direction.” It wasn't his time. That wasn't our story, and I knew it to be true. After I hung up, B and I grabbed some food but I wasn't hungry. We called it a night, crashed hard on our beds, and were on the Mexican road again at sunrise.

On the Road in Mexico, at Last

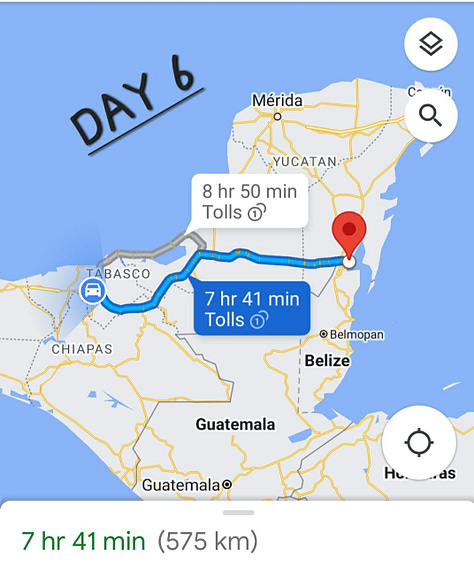

The rest of the trip went relatively smooth, apart from several near collisions on some rough and potted highways dodging cows and construction equipment, B sideswiping the side view mirror off of a Ford F150 while maneuvering the tight streets of Villahermosa and a brief extortion by local Mexican police in a small city I don't remember the name of when we detoured off the highway to procure some toll booth pesos. These events alone would provide most people enough to tell a captivating story, but they are just a side note in this one: one of the many “hiccups” along our 3,275-mile journey from Canada.

On the Mend

Thankfully, Dash's condition began to improve after that night. However, the hospital bill racked up. Unfortunately, my family's one month of travel insurance —which started when we all flew into Belize on April 30— lapsed while I was dealing with the distractions of becoming a Transmigrante. It was a hefty medical bill for a young family moving continents. Nevertheless, I would have paid ten times more if we had to.

The experience pretty well traumatized my wife, who was already reeling from two NICU births in which our first nearly died of MAS a year and a half prior. I have mostly glossed over her part of the story, a troubling ordeal further marked by a pertinent look into the harsh realities of the Belizean healthcare system. Yet, she is an incredibly strong, determined, and resilient woman. Her awareness, unconditional love, and grace in accepting life's hardships have enabled her to pull through and handle everything constructively. She is an inspiration and the love of my life. I am so grateful to know her and share a life with such a striking woman. (She is also a talented artist currently making waves in the contemporary art scene.) She often writes about her own life experiences and has plans, amongst the demands of her craft and family duties, to write a memoir: I don’t doubt that her experience with Dash will make it into her annals.

Close, But No Cigar

We made it through Mexico in three days, arriving in Chetumal in the early afternoon of the third day. Chetumal is in Quintana Roo, a free province in South Eastern Mexico that shares a border with Belize's northernmost city of Corozal. It was Saturday, and I was anxious and excited to get through and see my family. Dash was on the mend, but Lili was hesitant to leave the hospital, as bacterial infections can flare up unexpectedly. With me so close, she opted to stay. We decided I would get her on my way south to our final destination, Placencia, a small but lively tourist destination along the sprawling Belizean coast.

Upon settling into a dog-friendly hotel, I contacted my customs broker to let them know I would be at the border in the morning. “Great!” They replied, “We will meet you on Monday. Tomorrow is Sunday and customs at the border are closed.”

You have to be shitting me! I thought, another damn delay. The frustration welled up and I wanted to scream. But I kept it together. After all, I had so much to be grateful for: we arrived safely at the Belizean border, emotionally, tattered and exhausted, but physically well. Dash bounced back, Lili was happy, the dogs were well, and my trusty travel buddy B was in good spirits, as he had been for the duration of the trip.

A Silent Partner

I think this is an appropriate time to say a few things about B: a dear friend and the only one out of twelve who answered my call to accompany me on this trip. Initially, I planned to go alone, but pressure from my mother and wife led me to email family members and friends asking if they would be willing to come with me on the odd chance. A long-time friend (from way back in elementary school), he was also a steadfast fixture of this story. His running slogan, “It's all part of the experience,” uttered thrice daily, was a calming reminder of how we cannot control the happenstances in life. One must accept them calmly, take decisive action, and push through to a solution. If all else fails, try to enjoy the experience, or at the very least, get something constructive from it. These words settled my worries, relieved pressure, and helped me to think clearly.

Although primarily a silent character in this story, he was anything but. B proved invaluable: splitting the time behind the wheel, taking on the emotional burden alongside me, assisting with the dogs at borders, and translating basic Spanish so we could make some sense when almost everything didn’t. He also provided many opportunities for a laugh, which we desperately needed throughout the journey. I would also like to mention that he chose this trip as his vacation, giving up his annual two weeks of leisure to join me. Looking back, I see no other friend I would have rather had by my side.

More Unfortunate News

We hung out in Chetumal for the remainder of the weekend. On Sunday, B received the unfortunate news that his airline had canceled his flight and bumped him onto another one a day earlier, cutting even more time from his already depleted trip. B was supposed to have six days in Placencia. By the end of our journey, he only had one.

First thing Monday morning, we crossed into Belize, but not before the Mexican border officials detoured me through a gamma ray detection protocol. Apparently, they were suspicious I was trafficking guns, drugs, or enriched uranium. The scan was one thing, but the real bugger was it happened after waiting in a massive queue for nearly two hours, and after was promptly placed at the back of the line. All the while, B and the dogs, who weren't allowed to be on the bus with me throughout this process, stood sweltering in the hot sun.

Roshambo’d

We were almost clear of Mexico, but the country had one last kick in the cojones for me. Remember back in Brownsville when they stamped our passports with a seven-day visa before this debacle began? Well, it took us eight days to get through after all the delays, so I was charged a fine for both B and me for illegally staying longer than our visa allowed. At this point, I was fine throwing money at my problems to make them disappear.

As Slow As Belizean Molasses

The customs process in Belize, albeit slow, was smooth. After four hours and a slick hand from all the “palm greasing,” we headed south to Belmopan to see Lili and Dash. It was late by the time we arrived at the hospital, and wasn’t safe for us to traverse the dark mountainous roads leading south. I got a room for B and the dogs at a resort on the city outskirts, and I stayed with Lili and Dash at the hospital for one last night. In the morning, we collected B and the dogs and traversed the windy roads to Placencia.

We pulled up to our rental home and rushed in to see our son Jack, who had spent most of the last week with our friend Jess, who had accompanied us to assist while I was away. Dash went down for a nap, and we headed to the beach to spend time with our oldest.

We had made it, all was well, and we were grateful for it. It was a whirlwind week-and-a-half. We had nearly 3300 miles under our belts, had overcome unexpected challenges, and encountered helpful strangers.

Before this trip started, I was most concerned with mechanical issues slowing us down. But the trusty bus kept on trucking with no problems. When I reached out to the dude we purchased it from and told him we made it to our destination without issue (mechanical that is), he responded with surprise, claiming, “I didn’t think you’d make it.” Right, thanks man.

A Word to the Wise

If you're looking for information on moving south through Mexico with personal belongings, you've come to the right place. Yet, my experience was certainly the exception, not the rule. I doubt many North Americans migrating south have had to jump through the hoops I did. Nevertheless, I hope this story informed you and will lead you to consider hiring a customs broker to assist with getting through Mexico before your journey starts. Given what could happen if you're unaware, going the extra mile and spending the extra money on their services will save you time, money, and headaches—especially if you, too, are deemed a rare gringo Transmigrante.

If you enjoy my writing, you might also like Belize Foreigner Blog, the Lili Art Blog, or my award-receiving book Home in Good Hands. If you'd like to support this Substack and help me keep creating stories and essays about life abroad, consider subscribing, sharing, or making a small donation. And to those who already have—thank you. Your support means the world.

Post Script

I mentioned how hot it was on the bus several times throughout the story, and if you are wondering what I meant: it was hot enough to completely melt a bag of chocolate-covered almonds into a solid block!

Awesome read very entertaining I was sad when it was over

My wife and I are making the same (almost) trip in late December to Placencia. Your story, although very different from other ex-pat stories I have read and been told, was very informative. Thanks for sharing.

Maybe we can compare stories one afternoon at the Pickled Parrot.

We own our house in Placencia already having been down numerous times over ten years, and have just been anointed by the BTB as “official”QRP members.

Hopefully we have a better experience with the various powers that be in Mexico.

My mantra is: “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst!”

Hope to meet you in the new year !

Pete